Leaders of the Church of England have been scrambling to assure the faithful that their proposed £1 billion fund for slavery reparations will not come from donations to parishes.

Last year the Church of England announced it was establishing a £100 million fund for slavery reparations but later acknowledged there were plans afoot for the far larger target of £1 billion.

Running the Church of England is an expensive affair, and yearly operating costs stand at around a billion pounds sterling, which means that its proposed £1 billion in proposed slavery reparations will cost the equivalent of the Church’s entire annual budget.

The faithful are rightly concerned about this voluntary expense, since three-quarters of the Church of England’s operating expenses are funded directly by donations from worshippers in the Church’s 14,000 parishes.

Prior to the General Synod this weekend, House of Laity member Luke Appleton asked whether the Church Commissioners, who handle the finances of the church, will compensate dioceses and parishes that suffer a loss of donations in response to the reparations fund.

The deputy chairman of the commissioners, Bishop Stephen Lake of Salisbury, has answered that no parish money is earmarked for reparations but admitted there was no plan to compensate parishes for diminished donations.

“Our funding commitment will be sourced in its entirety from the Endowment Fund managed by the Church Commissioners,” he said in a statement. “None of the money given to a parish church will be used for this fund. None of the money will come from parish income.”

“We do not have any data about a material loss in giving due to the Church Commissioners’ work to address links to African chattel enslavement, although we have heard anecdotally that some givers may have chosen to withdraw support,” he added.

While Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby has praised the reparations as “the beginning of a multi-generational response to the appalling evil of transatlantic chattel enslavement,” not everyone is convinced of the wisdom of the scheme.

The Reverend Ian Paul of the Anglican Archbishops’ Council, for instance, has argued that the project is “anti-Christian” and smacks of “a death wish for the Church of England.”

This plan “appears to be based on an essentially racist reading of history – that white people are all bad and the oppressors, and black people are nothing more than victims,” Rev. Paul said. “This is insulting to both black and white.”

“It is anti-Christian,” he continued. “Unbelievably, it calls on the Church to repent for having preached the gospel.”

Paul also noted that African Christians, including the vast numbers of Anglicans in Africa, “will be very angry to read that.”

“It will imperil local ministry and mission,” he said. “Why would ordinary churchgoers continue to give to their local church when it appears we have these vast sums to throw around?”

General Synod member Prudence Dailey has echoed Rev. Paul’s opposition to the reparations, insisting that “the Church of England is effectively apologising for converting people to Christianity.”

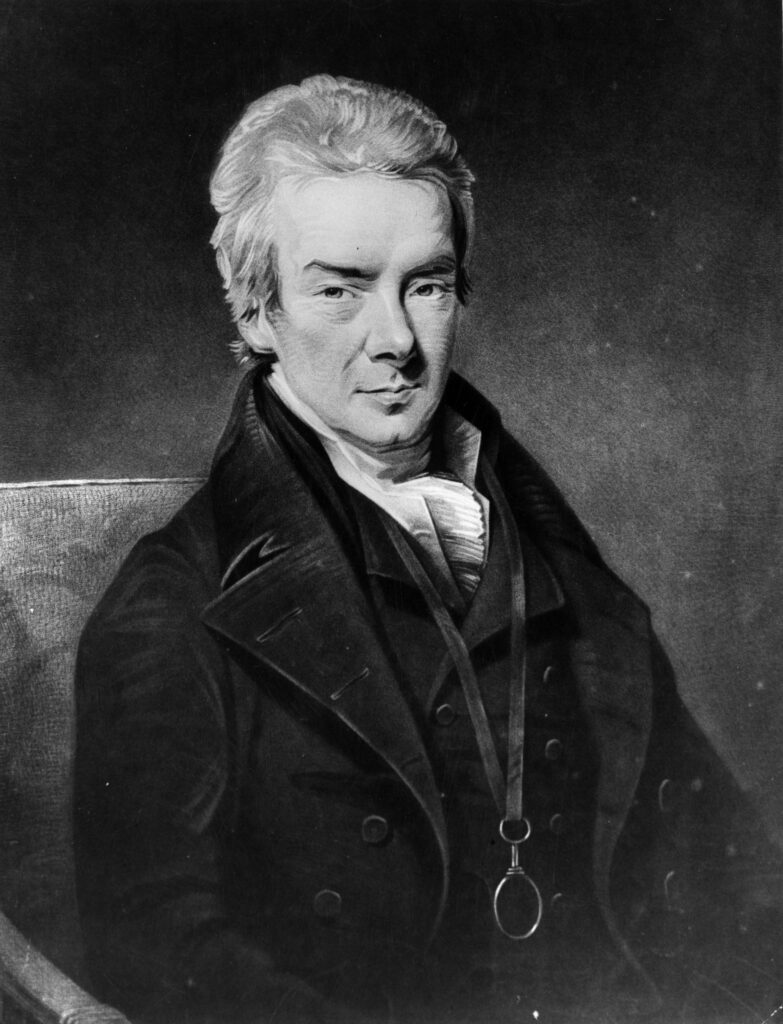

The Anglican slavery reparations plan is particularly ironic in that the greatest and most influential English abolitionist, William Wilberforce, was a devout and active member in the Church of England and credited his Christian faith as the motivating force behind his anti-slavery activism.

20th December 1888: British statesman William Wilberforce (1759 – 1833) who worked for the abolition of slavery, secured legislation prohibiting the trade and was a founder of the Anti-Slavery Society. Enslavement was abolished in Britain one month after his death. (Rischgitz/Getty)

As Anglican theologian James I. Packer has written, William Wilberforce “put evangelicalism on Britain’s map as a power for social change, first by overthrowing the slave trade almost single-handed and then by generating a stream of societies for doing good and reducing evil in public life.”

Because of Wilberforce’s work, Britain abolished slavery on August 1, 1834, some thirty years before it was abolished in the United States.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.